Course / training:

Method of Psychological Analysis

Psychological Model.

A 'Ten Factors Model' of human functioning

Short description

(1989 ff.).C.P. van der Velde.

3.4: Friday, May 19, 2008 21:07

Table of contents

1. Preface. Why this model?

2. Chosen approach in this project

3. Possibilities and limitations of influencing human functioning

4. Psychological model

5. Factors in human functioning

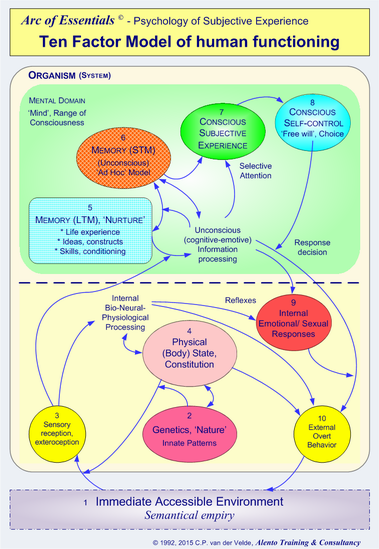

6. Diagram Ten Factor Model of human functioning.

7. Description of the factors

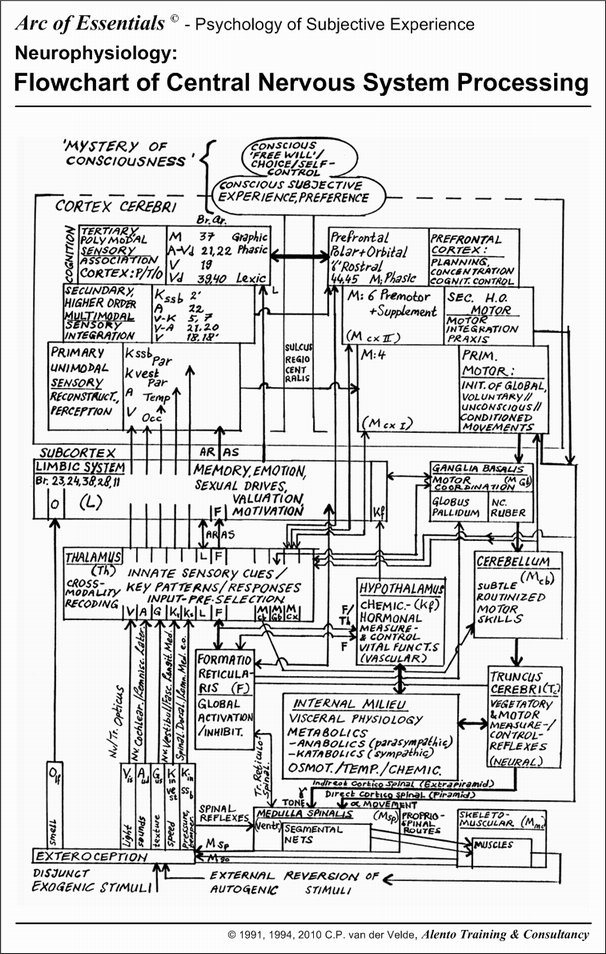

9. Flowchart Central Nervous System Processing.

10. Specialization of the hemispheres.

11. Levels in the psychic system

2. Chosen approach in this project

3. Possibilities and limitations of influencing human functioning

4. Psychological model

5. Factors in human functioning

6. Diagram Ten Factor Model of human functioning.

7. Description of the factors

(1) Environment

(2) Congenital patterns

(3) Sensory perception and body feeling

(4) Physical state

(5) Learned patterns

(6) (Unconscious) Psychic and mental processes, formation of ' ad hoc model'

(7) Conscious subjective experience

(8) Conscious Self-Control

(9) Internal responses

(10) External, behavioral expression

8. Notes on physiological reactions and external behavior(2) Congenital patterns

(3) Sensory perception and body feeling

(4) Physical state

(5) Learned patterns

(6) (Unconscious) Psychic and mental processes, formation of ' ad hoc model'

(7) Conscious subjective experience

(8) Conscious Self-Control

(9) Internal responses

(10) External, behavioral expression

9. Flowchart Central Nervous System Processing.

10. Specialization of the hemispheres.

11. Levels in the psychic system

1. Introduction. Why this model?

Like all living organisms, people have the ability to respond actively to their environment, and thus to respond to changing circumstances concerning their life and well-being. Naturally, it is advantageous to make those reactions more or less 'intelligent', ie sufficiently goal-oriented, efficient and effective for the benefit of our goals and needs. To be able to do this, just 'trying it out' (by trial-and-error) is often not efficient and may even be rather risky. That is why we have acquired - through millions of years of evolution - a capacity for information processing.

Equipped with this ability we form a model of our world, in which we store our experiences in a somewhat orderly fashion, in order to get an understanding of our impressions and experiences in their coherence. This enables us to recognize, explain and predict events in and around us - at least to a certain extent.

{For further reading on these topics, see for example:

(·) Principles of 'Modeling': the possibilities of knowledge, information and logic.

(·) Restrictions on human knowledge and judgment.

(·) Proof by falsification. Improving knowledge not through confirmation but refutation.

(·) Dimensions of information: data from different sources and levels.

(·) Premisses of the Method 'Practical Logic' ©. }

(·) Principles of 'Modeling': the possibilities of knowledge, information and logic.

(·) Restrictions on human knowledge and judgment.

(·) Proof by falsification. Improving knowledge not through confirmation but refutation.

(·) Dimensions of information: data from different sources and levels.

(·) Premisses of the Method 'Practical Logic' ©. }

Within the field of psychology attempts are made, among other things, to develop models about the ways in which people can (or can) make models. One interesting purpose of such a 'meta-model' may be to find out how human in general can use their models 'intelligently': that is goal-oriented, efficient and effective.

Gathering psychological knowledge turns out to be a job with numerous pitfalls. The first problem lies in the relationship between the researcher and the research area, respectively the built-up model. The 'meta-model' developed in psychology is, as a model of human modeling, at the same time part of human modeling: it is self-reflexive. The question is of course - and rather questionable - whether the human mind is capable of sufficiently 'overlooking' or 'understanding' its own functioning. "The snake can not be completely swallowed by the tail" (John S. Bell, 1973: pp.687-690; 1987: pp.41-42).

The second problem lies in the nature of the research domain. Although we can observe certain aspects of our psychological process within ourselves through introspection, this being an intrapsychic process is - apart from being selective, incomplete, and not necessarily reliable - not empirical in nature, exclusively personal and private, therefore not directly accessible to others. We may get to know the subjective experience of others to some extent, at most indirectly, through physical signals, communication and language. However, these are also very limited and fallible systems of information transfer.

As a result, it is hard not only to acquire reliable information about someone's psychic processes, but also to generalize it in a valid manner.

Because of these and other factors it is not easy to develop a theory that is demonstrably valid for the psychological processes of all people.

However, the problem goes deeper: it makes psychology a rather poorly decidable field of inquiry.

As a result, the knowledge and methodology of psychology still consists of an incredible diversity of opinions, ideas and approaches, often about the same phenomena. Many of these hypotheses, theories and conventions are often speculative, arbitrary, irrational, metaphorical or mythical. They are also rarely unambiguously interpretable, empirically verifiable and logically decidable, making them barely testable.

{For further reading on these topics, see for example:

(·) Patterns of noise in psychology.

(·) Logical diagnostics of psychology.

(·) Why Logic in Psychology. }

(·) Patterns of noise in psychology.

(·) Logical diagnostics of psychology.

(·) Why Logic in Psychology. }

The 'Ten Factors Model' is intended as an attempt to offer an unambiguous and reliable alternative to the kaleidoscopic variation of whole and half images of human in current psychology - ranging from the 'iconical ' academic ones to numerous New Age variants. Indeed, an ambitious goal, but surely worth the effort.

2. Chosen approach in this project

In developing this model, the first goal was of course to draw up a model of human functioning that has sufficient validity to offers a realistic and balanced image of the subject. A second goal was to achieve a meaningful, pragmatic balance between a reasonable level of completeness, and at the same time, a suitable degree of conciseness - or parsimony, in conformity with Occam's razor. As a third, the goal was to achieve at least a fair amount of global unification of the most important existing models and theories about human functioning.

The fourth, and most important goal was to construct a model that is really relevant, ie useful for practical applications.

The methodology in this development process was primarily obtained from logical criteria: both of 'natural' logic, and of the 'real', formal logic (also called mathematical logic).

{For further reading on these topics, see for example:

(·) Introduction 'Natural' logic. Applicable without formal logic.

(·) Introduction Formal logic. Advantages of formalization and basic forms of logic.

(·) Introduction Proposition logic. Reasoning with elementary statements.

(·) Introduction Predicate logic. Reasoning about individuals and categories.

(·) Logical criteria. Summary/ overview.

(·) Principles of Logical proof.

(·) Introduction Resolution logic. Sophisticated method of logical proof.

(·) Schedules Logical levels and criteria.

(·) Introduction Method for Causal analysis. Guidelines for cause-effect assessment, explanation, prediction. }

(·) Introduction 'Natural' logic. Applicable without formal logic.

(·) Introduction Formal logic. Advantages of formalization and basic forms of logic.

(·) Introduction Proposition logic. Reasoning with elementary statements.

(·) Introduction Predicate logic. Reasoning about individuals and categories.

(·) Logical criteria. Summary/ overview.

(·) Principles of Logical proof.

(·) Introduction Resolution logic. Sophisticated method of logical proof.

(·) Schedules Logical levels and criteria.

(·) Introduction Method for Causal analysis. Guidelines for cause-effect assessment, explanation, prediction. }

The first theoretical question was: what are actually the main lines which are relevant and crucial, and which are (almost) always valid? To answer the latter, the next question to ask became: what is at least necessary to assume to be true, when we want to draft a valid model of human functioning?

The logical answer to this is that we can best go by what at least is true or generally valid for the functioning of every single human individual: what can we consider to be the most dominant, most decisive and thus most relevant 'primary factors' in our functioning. We then arrive at (a) what we all have in common in any case - despite possible individual variations; and (b) what at the same time is always most generally verifiable and thus is most directly empirical perceptible. For both criteria a clear first candidate stands out: our nervous system.

The result, the 'Ten factors Model', is an attempt to offer a model of human functioning that at least combines two strengths:

(1) It is fairly unified: it unites the main components of a large number of existing psychological

theories and models;

(2) It is reasonably valid: it keeps close, preferably as close as possible, to the most decisive main lines in human information processing in accordance with the anatomical and functional major components within the nervous system; which are detectible in processes and stages of information flows, organ systems and their interactions through pathways and circuits.

(2) It is reasonably valid: it keeps close, preferably as close as possible, to the most decisive main lines in human information processing in accordance with the anatomical and functional major components within the nervous system; which are detectible in processes and stages of information flows, organ systems and their interactions through pathways and circuits.

3. Possibilities and limitations of influencing human functioning

A guideline in the formation of a model is the question for what purpose it must be used, in other words, what the intended application, use or function will be.

An important task of psychology is to provide guidelines that allow people to influence themselves or others purposefully in their behavior (effectiveness) and/or in their subjective experience (well-being). An important question for psychology is therefore: to what extent is such goal oriented influencing, steering or 'control' of human behavior actually possible? In other words: what are the possibilities and limitations in general, what is the 'room for maneuver', in influencing human functioning?

To find this out, first needed is determining the conditions under which external behavior and subjective experience undergo change. The latter question requires a psychological model.

4. Psychological model

The human organism can be regarded as an incredibly complex system in which countless factors play a role. In this system the effect of each individual factor is mediated by interaction with many others factors.

It is therefore useful to have an overview of the different factors in the (human) system. This includes a certain psychology, or a view on how people in general operate: a model of human functioning, a 'image of man'.

Below a new model of human functioning is presented: the 'Ten Factors Model of Human Functioning'. In a global, concise way, a simple, but useful summary of the model is given. It is a primarily pragmatic model, meant for practical psychological purposes.

In this model, key factors in human Functioning which must be taken into account for practical purposes, are presented in a coherent context. Hereby the most important processes, transformations and functions are described that determine the various phases, stages or states in which those factors may occur.

A large amount of research data has been applied in this model, hypotheses and models integrated, from different scientific fields:

(·)

(·)

(·)

(·)

(·)

Neurophysiology

(eg Milner, 1970; Cranenburgh, 1980; Kendal & amp; Schwartz, 1985; Martžnez Martžnez, 1980; Orlebeke etal, 1981; Voorhoeve, 1984; Squire & amp; Butters, 1984).(·)

Psychological function theory

(o.m .: Miller, Galanter & Pribram, 1960; Pribram, 1971; - 1974; - 1976).(·)

Cognitive psychology

(eg Neisser, 1967; - 1976; Legewie etal, 1972/1974; John, 1975; Ford, 1987; Kihlstrom, 1987).(·)

Artificial intelligence

(eg Schank & Colby, 1973; Schank, 1975; Schank & amp; Abelson, 1977; Charniak & amp; McDermott, 1985; Minsky, 1986).(·)

Neurolinguistics, 'Neuro-Linguistic Programming' (N.L.P.)

(eg: Dilts et al., 1979; Dilts, 1983).5. Factors in human functioning

Described below are what may be considered as the most important factors in human functioning, and the ways in which they function in relation to each other within the (human) system.

Some preliminary remarks:

(·) The factors and processes described here are to be distinguished but are not strictly separate.

(·) The presented classification in factors and processes is certainly not absolutely true, definite, or the only possible; but as a hypothetical model, it is well founded and substantiated, reasonably reliable and useful.

(·) The basic factors and processes (environment, observation, and beyond) constitute the boundary conditions that determine, like 'premisses', the scope of possible values and states of the later mentioned results, or 'conclusions' in internal and external reactions. This means that a certain chronological order can be distinguished between factors in their relative function of input, processing, and output.

(·) In reality, the processes mentioned will often take place simultaneously and in strong interaction with each other.

(·) The processes mentioned do not need to be all active simultaneously at all times. Someone in a coma for example, may be apt to some sensory, visceral and subcortical activity, but will often not show activation of 'higher' cerebral, cognitive or mental processes.

(·) In a more extensive description of the Ten Factors Model, the specific neurophysiological components (the neuronal correlates) of the factors and processes and their mutual relationships and interactions are described in more detail.

(·) The presented classification in factors and processes is certainly not absolutely true, definite, or the only possible; but as a hypothetical model, it is well founded and substantiated, reasonably reliable and useful.

(·) The basic factors and processes (environment, observation, and beyond) constitute the boundary conditions that determine, like 'premisses', the scope of possible values and states of the later mentioned results, or 'conclusions' in internal and external reactions. This means that a certain chronological order can be distinguished between factors in their relative function of input, processing, and output.

(·) In reality, the processes mentioned will often take place simultaneously and in strong interaction with each other.

(·) The processes mentioned do not need to be all active simultaneously at all times. Someone in a coma for example, may be apt to some sensory, visceral and subcortical activity, but will often not show activation of 'higher' cerebral, cognitive or mental processes.

(·) In a more extensive description of the Ten Factors Model, the specific neurophysiological components (the neuronal correlates) of the factors and processes and their mutual relationships and interactions are described in more detail.

6.

Diagram Ten Factor Model of human functioning.

|

|

Ten Factor Model of human functioning:

Numerous links between environment and reaction.

(A Simplified arrow diagram).

|

7. Description of the factors

(1) Environment

Situational factors. Including material and social conditions.

The first factor determining psychological functioning, is environment (external context, situation, biotope, nurture). These include material and social conditions or processes.

The environment provides matter and energy to the body.

A gradual distinction can be made between different influences:

The first factor determining psychological functioning, is environment (external context, situation, biotope, nurture). These include material and social conditions or processes.

The environment provides matter and energy to the body.

A gradual distinction can be made between different influences:

(A) Direct physical influences.

These are of a mechanical, chemical, electrical or magnetic nature (such as food, temperature, violence, various stimulation of the senses).

(B) Indirect physical influences.

In particular, this concerns the social environment. Such influences are realized through higher psychological and psychosocial processes involving signs and meaning, communication and language.

These are of a mechanical, chemical, electrical or magnetic nature (such as food, temperature, violence, various stimulation of the senses).

(B) Indirect physical influences.

In particular, this concerns the social environment. Such influences are realized through higher psychological and psychosocial processes involving signs and meaning, communication and language.

(2) Congenital patterns

Innate factors and predisposition. Congenital key characteristics, response patterns, talents and abilities.

The environmental influences are combined with innate characteristics or tendencies ('nature'). These are based on genetics of the individual. In the disposition of talents and tendencies of a person, different degrees can be distinguished, from general to specific:

It can be said that in general, the tendencies of the first type dominate the other ones in most respects.

The environmental influences are combined with innate characteristics or tendencies ('nature'). These are based on genetics of the individual. In the disposition of talents and tendencies of a person, different degrees can be distinguished, from general to specific:

(A) The universal genetic blueprint of humans, or general human potential.

(B) General gender differences.

(C) Ethnic or so-called 'racial' differences.

(D) The individual genetic profile.

(B) General gender differences.

(C) Ethnic or so-called 'racial' differences.

(D) The individual genetic profile.

It can be said that in general, the tendencies of the first type dominate the other ones in most respects.

(3) Sensory perception and body feeling

Direct observation. Through external and internal senses.

Under the influence of environmental factors, innate reflexes and physical condition, sensory observation takes place.

Through externally-sensory perception information about the environment is gathered in the various sensory modalities like seeing, hearing, touching, groping, sense of temperature and pain, pressure and balance, tasting, smelling, and so on.

Under the influence of environmental factors, innate reflexes and physical condition, sensory observation takes place.

(A) External-sensory perception (Exteroception, sensation).

(B) Internal body sensation (interoception, sensibility).

(B) Internal body sensation (interoception, sensibility).

Through externally-sensory perception information about the environment is gathered in the various sensory modalities like seeing, hearing, touching, groping, sense of temperature and pain, pressure and balance, tasting, smelling, and so on.

(4) Physical state

Internal state. Physical properties and processes.

By interaction of environmental factors and congenital tendencies, the physical state of the organism is determined (biological constitution, physiology, 'internal environment' or internal state). This includes physical health, fitness, muscle strength, muscle tone, funcionality of organs, and so on.

The physical condition can be seen as a 'snapshot' of all kinds of physiological processes (organic, vegetative and animate processes); including metabolism. The latter can be roughly devided into two types of processes:

The body condition is measured by internal body-perception (body sensation, interoception). To be distinguished are visceral feeling or visceroception; and muscle and movement feeling, or proprioception.

On basis of body perception the nervous system determines in particular what the (biological) needs of the organism are.

Change of body condition already leads on a subcortical level to the activation of innate reflexes , for example:

All these processes interact with higher processes in the nervous system and the brains.

By interaction of environmental factors and congenital tendencies, the physical state of the organism is determined (biological constitution, physiology, 'internal environment' or internal state). This includes physical health, fitness, muscle strength, muscle tone, funcionality of organs, and so on.

The physical condition can be seen as a 'snapshot' of all kinds of physiological processes (organic, vegetative and animate processes); including metabolism. The latter can be roughly devided into two types of processes:

(A)

Its function is preparing for action (preparatory).

Its mode concerns resting state (sedation); Slow down. It tends towards introversion.

This is the Comfort System, the Parasympathic system.

(B)

Its function is regulating activity (participatory).

Its mode concerns activation (arousal); Speed-up. It tends towards extroversion.

This is the Effort System, the (Ortho)Sympathic system.

Anabolism: Storage and construction.

Its function is preparing for action (preparatory).

Its mode concerns resting state (sedation); Slow down. It tends towards introversion.

This is the Comfort System, the Parasympathic system.

(B)

Catabolism: Combustion activity.

Its function is regulating activity (participatory).

Its mode concerns activation (arousal); Speed-up. It tends towards extroversion.

This is the Effort System, the (Ortho)Sympathic system.

The body condition is measured by internal body-perception (body sensation, interoception). To be distinguished are visceral feeling or visceroception; and muscle and movement feeling, or proprioception.

On basis of body perception the nervous system determines in particular what the (biological) needs of the organism are.

Change of body condition already leads on a subcortical level to the activation of innate reflexes , for example:

(A) Motor reflexes (Eg. The patellar tendon reflex).

(B) Central, subcortical reflexes (E.g. the orientation reflex).

(C) Vegetative reflexes due to emotional reactions (E.g. flushing), and sexual reflexes (e.g. erection, orgasm), etc ..

(B) Central, subcortical reflexes (E.g. the orientation reflex).

(C) Vegetative reflexes due to emotional reactions (E.g. flushing), and sexual reflexes (e.g. erection, orgasm), etc ..

All these processes interact with higher processes in the nervous system and the brains.

(5) Learned patterns

Long term memory content.

Memory which stores learning experiences.

As the organism reaches a sufficiently high level of activation, impulses from external and internal environment are distrubuted in the nervous system through all kinds of ascending (afferent) nerve tracks. Thus they will reach long term memory (L.T.M.). Memory content includes a reflection of the person's life experience or 'personal history'. There are various types of memory data (engrams):

The first two types of data together constitute the person's 'model of the world' or 'worldview' (including philosophy of life, 'picture of man', 'self image', and body image).

Memory which stores learning experiences.

As the organism reaches a sufficiently high level of activation, impulses from external and internal environment are distrubuted in the nervous system through all kinds of ascending (afferent) nerve tracks. Thus they will reach long term memory (L.T.M.). Memory content includes a reflection of the person's life experience or 'personal history'. There are various types of memory data (engrams):

(A) Data from direct experience.

A more or less chronological sequence of perceptions and feelings (episodic memory).

Mental content derived such as knowledge, ideas, fantasies, general rules, norms, values, preferences, plans, etc. (semantic memory).

These concern skills and habits in behavior, thinking, emotion, sexuality, social interaction, communication, etc. (strategies, 'programs', scripts, skills, etc.).

(D) Conditioned responses.

Associative combinations of action-reaction, stimulus-response, context and 'script'.

A more or less chronological sequence of perceptions and feelings (episodic memory).

1. External observations (exogenous).

2. Body feelings and sensations, and states of consciousness (endogenous).

(B) Data from indirect experience.2. Body feelings and sensations, and states of consciousness (endogenous).

Mental content derived such as knowledge, ideas, fantasies, general rules, norms, values, preferences, plans, etc. (semantic memory).

1. Rational constructions.

Abstract patterns and structural characteristics, hypotheses and generalizations; schemata, classifications, hierarchies and plans.

(In particular, this involves linear, temporal, convergent processes, typically within the left-side brain).

2. Non-rational constructions ('pseudo-sensations').

Fantasy representations, creative thinking, dream experiences, expectations, stereotypes, still rings and symbols.

(In particular, this involvs non-linear, spatial, divergent processes, typically within the right-side brain).

(C) Acquired reaction patterns.Abstract patterns and structural characteristics, hypotheses and generalizations; schemata, classifications, hierarchies and plans.

(In particular, this involves linear, temporal, convergent processes, typically within the left-side brain).

2. Non-rational constructions ('pseudo-sensations').

Fantasy representations, creative thinking, dream experiences, expectations, stereotypes, still rings and symbols.

(In particular, this involvs non-linear, spatial, divergent processes, typically within the right-side brain).

These concern skills and habits in behavior, thinking, emotion, sexuality, social interaction, communication, etc. (strategies, 'programs', scripts, skills, etc.).

(D) Conditioned responses.

Associative combinations of action-reaction, stimulus-response, context and 'script'.

The first two types of data together constitute the person's 'model of the world' or 'worldview' (including philosophy of life, 'picture of man', 'self image', and body image).

(6) (Unconscious) Psychological and mental processes, maintanance of 'ad hoc model'.

Active brain processes. Manifest cerebral information processing (cerebration).

Conscious and unconscious mental processes (mentation).

As soon as memory contents are activated, this leads to the activation of 'higher', central, psychological or mental processes, mainly in cortical brain areas. This concerns information processing and editing, together with decision making regarding internal and external tasks. It involves affective and cognitive processes, known as 'internal processing' or 'computation'. Including remembering and associating, thinking and reasoning, fantasizing and dreaming (the latter in particular during 'active' or REM sleep).

This central processing is decisive for both emotional reactions (including subjective well-being) and behavioral reactions (including effective functioning).

Mental processing is characterized by an immense and practically incomprehensible complexity. There are however certain elementary aspects that can be recognized.

As soon as memory contents are activated, this leads to the activation of 'higher', central, psychological or mental processes, mainly in cortical brain areas. This concerns information processing and editing, together with decision making regarding internal and external tasks. It involves affective and cognitive processes, known as 'internal processing' or 'computation'. Including remembering and associating, thinking and reasoning, fantasizing and dreaming (the latter in particular during 'active' or REM sleep).

This central processing is decisive for both emotional reactions (including subjective well-being) and behavioral reactions (including effective functioning).

Mental processing is characterized by an immense and practically incomprehensible complexity. There are however certain elementary aspects that can be recognized.

(A)

A variety of data and factors make upn the input for the mental operations: such as environmental influences, innate reflexes, physical processes, observational data and memory content. These provide the 'raw materials' for the activity of higher-level central physical and mental processes, primarily within the cortical brain.

(B)

The organism is continuously confonted with the challenge to produce an adequate response, be it internal or external, to the given situation. This from the point of view of certain objectives and priorities (which can be biological, emotional, social, etc.). The central processing determines both emotional reactions (including subjective well-being) and behavioral responses (including effective performance).

(C)

A logically - and practically - necessary step is, therefore, the formation of a concept, or so-called ad hoc model of the current situation. This consists of an (abstract) representation of the organism itself in relation to the setting of that moment. The construed representation of the current situation serves as a guidance for the determination of adequate emotional and behavioral responses tn the given situation. It is made up of 'internal' or mental representations (' internally generated experience', or 'internals') that are momentarily active, or manifest. The latter we usually call thoughts, ideas, memories, fantasies, reasoning, emotions, values, beliefs, assumptions, dreams, etc..

(D)

The 'ad hoc model is constantly fabricated and modified through largely unconscious information processing. These processes include information-processing, and decision making (affective and cognitive processes, 'internal processing' or ' computation'). This includes recollection and associative thinking, reasoning, fantasizing and dreaming (the latter especially taking place during 'active' or REM sleep).

These processes are mainly driven by cognitive operators and programs available that are part of the specific activity of the psychic apparatus.

(E)

The active processes, together with their outcome, the 'ad hoc model', are part of variable contents of the so-called 'working memory' or Short Term Memory (S.T.M.).

The contents of the S.T.M. is primarily unconscious, but partly also consciously accessible. The greatest part of the contents of the S.T.M. however, is always unconscious (subliminal): the unconscious domain. This unconscious content does have a great influence on the task performance of the person.

The whole of these processes and contents is also called 'the unconscious mind' or 'intuition'.

(F)

Only a relatively very small part of the contents of the S.T.M. can be experienced consciously in principle ( supraliminal): its 'conscious range' (see below).

Basic ingredients.

A variety of data and factors make upn the input for the mental operations: such as environmental influences, innate reflexes, physical processes, observational data and memory content. These provide the 'raw materials' for the activity of higher-level central physical and mental processes, primarily within the cortical brain.

(B)

Core function.

The organism is continuously confonted with the challenge to produce an adequate response, be it internal or external, to the given situation. This from the point of view of certain objectives and priorities (which can be biological, emotional, social, etc.). The central processing determines both emotional reactions (including subjective well-being) and behavioral responses (including effective performance).

(C)

Construction of an Ad hoc model.

A logically - and practically - necessary step is, therefore, the formation of a concept, or so-called ad hoc model of the current situation. This consists of an (abstract) representation of the organism itself in relation to the setting of that moment. The construed representation of the current situation serves as a guidance for the determination of adequate emotional and behavioral responses tn the given situation. It is made up of 'internal' or mental representations (' internally generated experience', or 'internals') that are momentarily active, or manifest. The latter we usually call thoughts, ideas, memories, fantasies, reasoning, emotions, values, beliefs, assumptions, dreams, etc..

(D)

Mental operations.

The 'ad hoc model is constantly fabricated and modified through largely unconscious information processing. These processes include information-processing, and decision making (affective and cognitive processes, 'internal processing' or ' computation'). This includes recollection and associative thinking, reasoning, fantasizing and dreaming (the latter especially taking place during 'active' or REM sleep).

These processes are mainly driven by cognitive operators and programs available that are part of the specific activity of the psychic apparatus.

(E)

Working memory.

The active processes, together with their outcome, the 'ad hoc model', are part of variable contents of the so-called 'working memory' or Short Term Memory (S.T.M.).

The contents of the S.T.M. is primarily unconscious, but partly also consciously accessible. The greatest part of the contents of the S.T.M. however, is always unconscious (subliminal): the unconscious domain. This unconscious content does have a great influence on the task performance of the person.

The whole of these processes and contents is also called 'the unconscious mind' or 'intuition'.

(F)

'Conscious range'.

Only a relatively very small part of the contents of the S.T.M. can be experienced consciously in principle ( supraliminal): its 'conscious range' (see below).

(7) Conscious subjective experience

Bubble of Perception. Including awareness of preferences, goals and priorities.

Through conscious and unconscious processes of selective attention, a relatively small portion of mental processes and contents from 'unconscious domain' may become conscious ( supraliminal). The conscious range includes conscious subjective experience (' bubble of perception'). This concerns e.g. the degree of emotional well-being, or subjectively experienced quality of life, and presumably also experiences of meaning or spirituality.

The phenomenon of conscious experience still is in a high rate inexplained and in certain respects of a mysterious nature.

Through conscious and unconscious processes of selective attention, a relatively small portion of mental processes and contents from 'unconscious domain' may become conscious ( supraliminal). The conscious range includes conscious subjective experience (' bubble of perception'). This concerns e.g. the degree of emotional well-being, or subjectively experienced quality of life, and presumably also experiences of meaning or spirituality.

The phenomenon of conscious experience still is in a high rate inexplained and in certain respects of a mysterious nature.

(·) Every conceivable form of conscious experience is completely and 'absolutely' dependent of a certain

ability to have a state of 'subjective consciousness'.

(·) Conscious experience is at the same time highly dependent of organic factors and processes in the body and nervous system.

(·) There are however no neurophysiological correlates, connections or causal links to be found that provide a full explanation for all specific - and partly unique - attributes of consciousness (such as qualia, quality of experience and the like).

(·) Conscious experience is at the same time highly dependent of organic factors and processes in the body and nervous system.

(·) There are however no neurophysiological correlates, connections or causal links to be found that provide a full explanation for all specific - and partly unique - attributes of consciousness (such as qualia, quality of experience and the like).

(8) Conscious self-steering

Available margin of conscious choice.

Subsequently, a portion of conscious experience can be susceptible to feedforward adjustment or regulation on basis of conscious choices of the person with respect to his/her own functioning.

This comprises the margin of available conscious choice, or 'free will'. That means we are able to exercise a certain degree of free choice, self-management and self-determination.

The conscious range of choice is completely and 'absolutely' dependent of a certain degree of conscious awareness, viz. conscious perception, or mental representation of (supposed) options available at that moment. For freedom of choice, therefore, the capacity for conscious subjective experience is in any case required.

Conscious subjective experience and free will together may be considered as the 'conscious domain'.

The ability of conscious self-control or 'free will' is even more difficult to explain than that of subjective consciousness, because, taken in a 'literal' sense, it is incompatible with deterministic causality: it would 'break through' cause-effect chains. Whether there is a direct, causal or mechanical relationship with organic factors is entirely unclear.

What is clear, in any case, is that there is a difference between processes that are in a given situation voluntary and those involuntary. It is also clear that the accessibility of reaction patterns for conscious self-management is not constant but varies depending on numerous other factors. We therefore have no 'almighty' free will, but rather a certain limited, subjective 'room for maneuver of choice'. We can experience that this margin varies: it can decrease or increase depending on the condition of the previous psychological factors: situation, physical state, learning experiences and cognition.

Logically, a number of sub-processes are required for a complete 'conscious choice' with respect to a certain option to act on. It is interesting to see which ones they are and what functions they have.

The immediate effect of conscious choice is probably mainly adjustment of already active (especially unconscious) mental processes within short-term memory (STM). As a result, it will mainly indirectly influence the formation of emotional, sexual and behavioral reactions.

Subsequently, a portion of conscious experience can be susceptible to feedforward adjustment or regulation on basis of conscious choices of the person with respect to his/her own functioning.

This comprises the margin of available conscious choice, or 'free will'. That means we are able to exercise a certain degree of free choice, self-management and self-determination.

The conscious range of choice is completely and 'absolutely' dependent of a certain degree of conscious awareness, viz. conscious perception, or mental representation of (supposed) options available at that moment. For freedom of choice, therefore, the capacity for conscious subjective experience is in any case required.

Conscious subjective experience and free will together may be considered as the 'conscious domain'.

The ability of conscious self-control or 'free will' is even more difficult to explain than that of subjective consciousness, because, taken in a 'literal' sense, it is incompatible with deterministic causality: it would 'break through' cause-effect chains. Whether there is a direct, causal or mechanical relationship with organic factors is entirely unclear.

What is clear, in any case, is that there is a difference between processes that are in a given situation voluntary and those involuntary. It is also clear that the accessibility of reaction patterns for conscious self-management is not constant but varies depending on numerous other factors. We therefore have no 'almighty' free will, but rather a certain limited, subjective 'room for maneuver of choice'. We can experience that this margin varies: it can decrease or increase depending on the condition of the previous psychological factors: situation, physical state, learning experiences and cognition.

Logically, a number of sub-processes are required for a complete 'conscious choice' with respect to a certain option to act on. It is interesting to see which ones they are and what functions they have.

The immediate effect of conscious choice is probably mainly adjustment of already active (especially unconscious) mental processes within short-term memory (STM). As a result, it will mainly indirectly influence the formation of emotional, sexual and behavioral reactions.

(a) Retroactive effect (feedback):

Deliberate 'real-time self-correction', through adjustment of selective attention, selective memory, and cognitive construction (like logical calculation or creative imagination).

(b) Forward effect (feed forward):

Global control of the next choices, with respect to cognitive processes, internal physical reactions, and motor behavior.

The notion of 'free will' is an essential condition for broader human qualities that are more commonly

referred to in social life with terms such as:Deliberate 'real-time self-correction', through adjustment of selective attention, selective memory, and cognitive construction (like logical calculation or creative imagination).

(b) Forward effect (feed forward):

Global control of the next choices, with respect to cognitive processes, internal physical reactions, and motor behavior.

(·) 'Willpower'.

(·) Will determination, ability.

(·) Power over self, self-control, self-determination.

(·) Personal independence.

(·) Imputability, therefore liability for ones own behavior.

Within the scope of freedom of choice lies the free choice to acknowledge ones own freedom of choice.

Thus, the conscious 'choice to chose' is decisive for the scope of personal responsibility.(·) Will determination, ability.

(·) Power over self, self-control, self-determination.

(·) Personal independence.

(·) Imputability, therefore liability for ones own behavior.

(9) Internal reactions

Subcortical and peripheral responses.

As a result of mental processes in the cortical brain, which are partly conscious but largely of a unconscious kind, physiological responses arise. These are originating mainly in subcortical regions of the brain, and consist of a combined activation of 'conditioned' (learned) responses, and 'automatic' (innate) reflexes. They find their way through peripheral, vegetative systems, activating intestines, guts and glands.

In the first place they give rise to 'internal' reactions:

As a result of mental processes in the cortical brain, which are partly conscious but largely of a unconscious kind, physiological responses arise. These are originating mainly in subcortical regions of the brain, and consist of a combined activation of 'conditioned' (learned) responses, and 'automatic' (innate) reflexes. They find their way through peripheral, vegetative systems, activating intestines, guts and glands.

In the first place they give rise to 'internal' reactions:

(A)

Through the central nervous system, e.g. global activation or sedation.

(B)

In the peripheral, vegetative nervous system, e.g. emotional and/or sexual excitation (associated with altered respiration, heart beat, blood pressure, etc.).

Neurological reactions.

Through the central nervous system, e.g. global activation or sedation.

(B)

Organic reactions.

In the peripheral, vegetative nervous system, e.g. emotional and/or sexual excitation (associated with altered respiration, heart beat, blood pressure, etc.).

(10) External, behavioral expression

Motor response. External behavior.

Finally, externally observable (overt) behavior is determined, also on a subcortical level. In particular, this involves motor skills, self-expression and communication.

This is regulated through the peripheral motor nervous system, and activating muscles and glands. These expressions mainly consist of motor responses, for example, moving, behaving, phonation, speaking, and so on.

Finally, externally observable (overt) behavior is determined, also on a subcortical level. In particular, this involves motor skills, self-expression and communication.

This is regulated through the peripheral motor nervous system, and activating muscles and glands. These expressions mainly consist of motor responses, for example, moving, behaving, phonation, speaking, and so on.

8. Notes concerning physiological responses and external behavior.

Both 'internal' physiological responses (ad 9) and 'external' behaviors (ad 10) are activated through efferent descending nerve tracks from brains and spinal cord. Also, both types of reactions may (a) originate from congenital reaction patterns, but (b) they can also stem from 'stored', conditioned and 'routined' reactions, and (c) in addition (consciously or unconsciously), they may emerge as newly constructed reactions.

They can come to expression through various channels:

(I) Glands: for example, secretion, perspiration, tears, etc..

(II) Skin: for example, blood flow (flushing), goosebumps, etc..

(III) Muscles: for example, movement, tension (tonus), sound (voice), power and pressure.

Subsequently, each kind of reaction has a certain influence on the overall physiological state,

and thus on the information collection through exteroception and interoception.(II) Skin: for example, blood flow (flushing), goosebumps, etc..

(III) Muscles: for example, movement, tension (tonus), sound (voice), power and pressure.

9. Flowchart of Central Nervous System Processing.

|

|

Ten Factors Model of human functioning:

Flow chart of Central nervous system.

(Simplified diagram).

|

10. Specialization of the hemispheres

.With respect to the entire nervous system, a global distribution can be distinguished in functionality between two systems. This dichotomy constitutes a continuation of the systems that play a role in metabolism (as discussed above under the factor Physical state).

On the one hand, we see (a) the preparatory function, directed towards internal organization, storage and construction, and the tendency to introversion; and on the other hand, we find (b) the participatory function, directed towards activation (arousal), and the tendency to extraversion.

A similar, global dichotomy can be recognized in the functioning of the large brain (telencephalon or cerebrum). This is formed by the two halves of the brain, the so-called cerebral hemispheres ( hemispherium cerebri), which are separated by the longitudinally situated groove ( fissura longitudinalis cerebri). Both brain halves show to a certain extent a typical specialization (so-called laterality).

The 'dominant' or 'language' brain, lies with most people that are right-handed (about 95%) at the left side of the body, and in that case controls the right half of the body; the 'non-dominant' brain is usually on the right and then controls the right half of the body.

Below is an overview of a number of characteristic, specialized functions that are often attributed to the hemispheres.

The details and differences mentioned here deserve however a few remarks. With respect to location, development, operation and other characteristics of the functions it almost always concerns relative differences between the hemispheres. In addition there is, as with everything in physiology and nervous system, a wide variety between individuals in almost all aspects of anatomy and functionality which can be distinguished. Finally, there still exists much debate and controversy between†experts and researchers about the precise facts of this specialization.

(a)

(b)

The dominant hemisphere.

(·) System: Effort system. Related to: (Ortho-) Sympathicus.

(·) Aimed at: steering, control, activity; extraversion, exteroception; motor skills and proprioception;

(·) Mode: concentration, alertness, waking consciousness;

(·) Tendency to: distance, calculation, quantity;

(·) System: cognition, rationality, logic; structure, order, abstract patterns; constancy;

(·) Modality: relatively more time-oriented (temporal);

(·) Organization: linear, sequential;

(·) Mental specialization: anchoring in time, dissociated memory, 'timeline';

(·) Information processing: convergent; conjunctive, restrictive, selective, reductive, analytical, rational, digital;

(·) Specific skills: recognition of contours and colors; language consumption: listen, read, decoding; language production: speak, write, verbal thinking; abstract construction;

(·) Aimed at: steering, control, activity; extraversion, exteroception; motor skills and proprioception;

(·) Mode: concentration, alertness, waking consciousness;

(·) Tendency to: distance, calculation, quantity;

(·) System: cognition, rationality, logic; structure, order, abstract patterns; constancy;

(·) Modality: relatively more time-oriented (temporal);

(·) Organization: linear, sequential;

(·) Mental specialization: anchoring in time, dissociated memory, 'timeline';

(·) Information processing: convergent; conjunctive, restrictive, selective, reductive, analytical, rational, digital;

(·) Specific skills: recognition of contours and colors; language consumption: listen, read, decoding; language production: speak, write, verbal thinking; abstract construction;

(b)

The non-dominant (submessive) hemisphere.

(·) System: Comfort system. Related to: Parasympathicus.

(·) Aimed at: experience, sensation, emotion, entertainment; introversion, interoception; sensory perception and sensibility;

(·) Mode: diffuse attention, relaxation, rest or moderate activity; sleep, dreaming, hypnotic trance;

(·) Tendency to: (personal) involvement, evaluation, quality;

(·) Systematics: perception, emotion; content, dynamics;

(·) Modality: relatively more spatially oriented;

(·) Organization: simultaneous, multi-dimensional;

(·) Mental specialization: spatial overview ('panorama' vision); left-right coordination, body diagram, physical self-image;

decoupling time, associated ('integral') memory, regression;

(·) Information processing: divergent; disjunctive, explorative, associative, expansive, creative, 'intuitive'; analogue;

(·) Specific skills: recognition of faces, emotions, empathy, (deemed) 'mind reading', projection; music experience, endogenous "self" expression (non-verbal or tonal /paralinguistic); creative imagination, artistic expression: poetry, singing, making music, dancing, drawing /painting, sculpturing, ...

(·) Aimed at: experience, sensation, emotion, entertainment; introversion, interoception; sensory perception and sensibility;

(·) Mode: diffuse attention, relaxation, rest or moderate activity; sleep, dreaming, hypnotic trance;

(·) Tendency to: (personal) involvement, evaluation, quality;

(·) Systematics: perception, emotion; content, dynamics;

(·) Modality: relatively more spatially oriented;

(·) Organization: simultaneous, multi-dimensional;

(·) Mental specialization: spatial overview ('panorama' vision); left-right coordination, body diagram, physical self-image;

decoupling time, associated ('integral') memory, regression;

(·) Information processing: divergent; disjunctive, explorative, associative, expansive, creative, 'intuitive'; analogue;

(·) Specific skills: recognition of faces, emotions, empathy, (deemed) 'mind reading', projection; music experience, endogenous "self" expression (non-verbal or tonal /paralinguistic); creative imagination, artistic expression: poetry, singing, making music, dancing, drawing /painting, sculpturing, ...

11. Levels in the psychic system

Within the psychic system, essentially different levels are to be distinguished.

I.

This is part of the material universe An Sich. It has intrinsic ordering, including causal relations in a narrower sense.

Physical phenomena are not immediately apparent, only through an active nervous system, application of logical relations, and consciousness.

II.

Also called logical domain. Abstract patterns which constitute information in the narrower sense. Is purely quantitative. One difference = 1 bit, implies the unfolding of the entire systematics of formal logic, (thus) including mathematics (ie the ultra-exponential combinatorial explosive unfolding of the maximal matrix of all possible logical relations, reasoning schemes and derivations).

III.

The area of subjective consciousness. Is purely qualitative, it includes perceptiual values, qualities or qualia, and freedom of choice.

Physical domain.

This is part of the material universe An Sich. It has intrinsic ordering, including causal relations in a narrower sense.

Physical phenomena are not immediately apparent, only through an active nervous system, application of logical relations, and consciousness.

(1) The 'brain mass'. This consists of neuro-physical substance. It is the organic, material matter

of which the physical brain is composed (the 'hardware').

It is relatively distinct from order or structure.

(2) 'Brain structure'. In a strict sense, this means neuro-physical structure: construction, anatomy or architecture of the physical brain. It is the arrangement of neuro-physical substance ad (1), in space dimensions.

(3) 'Brain function'. Neurophysiological structure, systematics, consisting of functions, (causal) mechanisms. The 'operating' of the psychic system in the longer term we assume to be established within (2). It can be described in terms of procedures ('recipes', programs, or software).

(4) 'Brain processes'. Neurophysiological processes. This is (3) in action, along the time line, acting on (1), but also on (2)! It is of course continuously varying.

(5) 'Brain status'. Neurophysiological state: the physical state of the brain, ad (1), (2), (3) and (4), at any point in time. It is incidental in nature.

The elements (1), (4) and (5) are relatively variable. Elements (2) and (3) are globally seen

relatively constant or 'structural', at least at macro level; but at the micro and nano level also quite variable.

(2) 'Brain structure'. In a strict sense, this means neuro-physical structure: construction, anatomy or architecture of the physical brain. It is the arrangement of neuro-physical substance ad (1), in space dimensions.

(3) 'Brain function'. Neurophysiological structure, systematics, consisting of functions, (causal) mechanisms. The 'operating' of the psychic system in the longer term we assume to be established within (2). It can be described in terms of procedures ('recipes', programs, or software).

(4) 'Brain processes'. Neurophysiological processes. This is (3) in action, along the time line, acting on (1), but also on (2)! It is of course continuously varying.

(5) 'Brain status'. Neurophysiological state: the physical state of the brain, ad (1), (2), (3) and (4), at any point in time. It is incidental in nature.

II.

Abstract-patterns domain.

Also called logical domain. Abstract patterns which constitute information in the narrower sense. Is purely quantitative. One difference = 1 bit, implies the unfolding of the entire systematics of formal logic, (thus) including mathematics (ie the ultra-exponential combinatorial explosive unfolding of the maximal matrix of all possible logical relations, reasoning schemes and derivations).

(1) Ongoing information processing. The operations that are currently manifest. Changes and rearrangings

of active content of short-term memory.

(2) The more variable data available at any point in time. 'Content', or machine states.

(3) Logical relations between existing and possible data on psychological content within the psychic system. Including the applicable logico-semantic relations, or 'sign-meaning relationships' within the cognitive system ( belief system) of the person.

All parts of the information domain (II) are only hypothetically applicable to the neurophysical domain (I).

They can be derived, inter alia, from post hoc analysis and comparison of observations of (I)

and (inter) subjective experiences of (III).(2) The more variable data available at any point in time. 'Content', or machine states.

(3) Logical relations between existing and possible data on psychological content within the psychic system. Including the applicable logico-semantic relations, or 'sign-meaning relationships' within the cognitive system ( belief system) of the person.

III.

Intrapsychic domain.

The area of subjective consciousness. Is purely qualitative, it includes perceptiual values, qualities or qualia, and freedom of choice.

(1) Conscious subjective experience (Bubble of Perception).

(2) Conscious free-will decision Conscious self-management, self-determination or 'free choice'. This includes the option to recognize and exploit this freedom of choice: ie the margin of (self) responsibility.

(2) Conscious free-will decision Conscious self-management, self-determination or 'free choice'. This includes the option to recognize and exploit this freedom of choice: ie the margin of (self) responsibility.

These three domains play a role in every notion of information in a general sense. But each has unique characteristics, and therefore none of these dimensions can be traced back to another.

The psychic system can be regarded as a bio-chemo-electric machine up to and including the first two levels, or ' bio-robot' - but not above these.

{More about the characteristics and relations of information dimensions; see:

(·) Dimensions of information. Data from different sources and levels.

(·) Dimensions and factors of function according to

(·) Dimensions and factors of information to

(·) Dimensions of information. Data from different sources and levels.

(·) Dimensions and factors of function according to

Arc or Essentials ©

. Coherence and interaction.(·) Dimensions and factors of information to